Paul Curwell

CPP, CISSP, CFE*

What is product diversion?

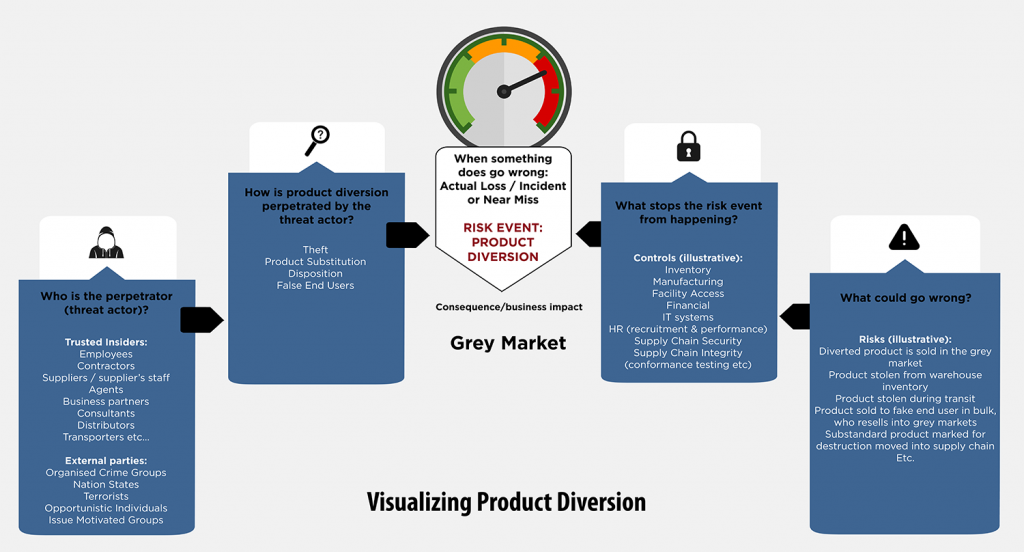

Product diversion, also known as “illicit diversion”, “refers to goods that are redirected from the manufacturer’s intended area of sale or destination to a different geography or distribution channel” (Trent and Moyer, 2013). The term “product diversion” is used interchangeably with “grey market” by some authors, despite one term referring to a fraudulent act and the other where the proceeds of that fraudulent act are sold. As referenced, one outcome of product diversion is that diverted product may be sold into grey (unauthorized) markets, in breach of a manufacturer’s sales contracts for that geographical location. This causes margin erosion for manufacturers, erodes legitimate distributors of their market share and deprives them of sales revenue, and can damage the brand through invalid warranties and returns policies for consumers. To minimize product diversion, we must first understand how it happens and who perpetrates it before implementing appropriate mechanisms to detect it. Here we lay out how product diversion can occur at a more fundamental level, identify the individual “elements” of a diversion event, and then look at how these can be used to develop a detection or monitoring program to identify when diversion is / has occurred as early as possible to facilitate an effective response.

How have we historically prevented product diversion?

According to Post and Post in Global Brand Integrity Management: How to Protect Your Product in Today’s Competitive Environment, there are four main drivers of product diversion: (1) theft during manufacture, transport, storage or point of sale, (2) false end users, particularly relevant for bulk purchases where volumes of product are bought at a discount and then resold, (3) substitution, or swapping legitimate product with substandard or counterfeit product into the supply chain, and (4) disposition, taking product marked for destruction and passing it off as conforming and fit for sale. As with any fraud or security issue, the risk of product diversion is typically managed through a comprehensive program encompassing policies, procedures, risk assessments, organizational culture, training & awareness, internal controls, and control assurance. However, unlike traditional fraud and supply chain security programs, product diversion programs need to be broader and encompass activities such as “end user due diligence” (to ensure an end user is who they claim to be and their intended purpose is legitimate), and a “market surveillance” program to monitor where their product is being sold, by whom, and for how much (pricing surveillance).

Depending on where the diversion event happens in the supply chain, perpetrators can be (a) an external party with no direct connection to the product manufacturer (e.g. customers, criminals) or (b) trusted insiders (e.g. employees, contractors, agents, suppliers) as well as insiders in collusion with external parties. The management of insider threats is made harder in product diversion because of the number of third parties, and even fourth parties, and the global nature of the supply chain. Minimizing product diversion is challenging given it is dependent on the standards, policies, culture and expectations of a product manufacturer being aligned with its third parties, and their third parties, including through contractual mechanisms and business partner selection processes. This complexity means that it is not feasible to rely on prevention alone: threat identification and detection is now a critical component of any anti-product diversion program.

Enter convergence: building a next generation capability to detect product diversion

The field of product protection is not unique in experiencing the challenges associated with detecting threats across an ecosystem of third parties, disparate systems and data sources, and geographies. In fact, these challenges are common across all fraud and security-related functions whether manufacturers, banks or law enforcement agencies. Unfortunately, our historically siloed practices, where data points are held in disparate systems managed by different functional teams and rarely connected, are increasingly inadequate to detect serious or sophisticated crime.

In response, organizations are increasingly adopting in-house intelligence programs to identify threats and drive detection and response efforts, building integrated data models and detection systems that cut across organizational silos, and operating models that maximize collaboration, cooperation and communication to enable a timely and effective “whole-of-organization” response. The term for this response is “security convergence”, which refers to the merging of fraud, physical security, cyber security and other risk and operational functions which are traditionally siloed and operate in isolation, into one cohesive entity. The benefit of convergence is that it allows you to detect a threat actor’s interactions with your organization “end to end”- from the minute they initiate contact through to the “attack” and subsequent escape. This increases the likelihood of early detection and effective response.

While convergence has been discussed as a theory since the early 2000’s, it has only become a reality over the past few years as technology and our capacity to process “big data” has evolved. Globally, banks are leading the push for convergence having big budgets and being directly impacted by regulatory fines and sanctions. However, just as these approaches can help banks, they can also help manufacturers and product owners address product diversion by detecting potential diversion events and enabling timely incident response and investigation.

So where do you start on this journey?

Building a next-generation “converged” detection system is a four-step process which requires a multidisciplinary team with skills including IT, data science / data analytics and corporate security. Fortunately, many companies increasingly have access to these advanced analytics skills through their cybersecurity functions or marketing departments.

While these measures will not solve the counterfeit problem, they help to reduce the volumes of conforming and partially-conforming product being diverted into non-approved markets, which will in turn have a positive impact on overall supply of diverted product in grey markets.

*Paul Curwell is a Director in Deloitte’s Forensic practice in Australia where he works with public and private sector clients to develop intelligence and investigative analytics capabilities to improve the management of fraud, security and business integrity risks. He is a co-author of “Terrorist Diversion: A Guide to Prevention and Detection for NGOs” published by Routledge (2021).

THE BRAND PROTECTION PROFESSIONAL |JUNE 2021 | VOLUME 6 NUMBER 2

2021 COPYRIGHT MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES

THE BRAND PROTECTION PROFESSIONAL |DECEMBER 2017 | VOLUME 2 NUMBER 4

2017 COPYRIGHT MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES