RISK OF CYBER SUPERSPREADERS AND INFLUENCERS ON PRODUCT INTEGRITY: COVID-19 AND BEYOND

Tim K. Mackey, MAS, PhD

Associate Professor at UC San Diego in the School of Medicine, the Director of the Global Health Policy and Data Institute and the CEO and co-Founder of S-3 Research LLC

Cyber Superspreaders?

In a previous article in the Brand Protection Professional, I described the characteristics of the current COVID-19 Infodemic and why the confluence of digital misinformation, cybercrime, counterfeiting and other forms of online fraud are now an everyday challenge in the world’s fight against the worst pandemic since the 1918 Spanish Flu (“COVID-19: A Cyber Syndemic” BPP, June 2020). With the daily number of COVID-19 cases reaching record highs in the United States (over 100,000 as of the beginning of November 2020), the continuing spread of the disease and the misinformation and frauds that surround it continue to hamper pandemic response efforts, including ensuring the integrity of current and future health products meant to contain it, which are increasingly marketed and sold online.

In the context of better understanding the epidemiology of this infectious disease, “superspreader” events (where a single event or individual can be traced back to infecting an unusually high number of secondary cases) have been recognized as a key risk factor for sustained and rapid transmission of COVID-19 (Lloyd-Smith et al, 2005). In fact, these superspreader events are not a new phenomenon; during the 2003 SARS outbreak a single index patient in a Hong Kong hotel was identified as the source for acquired infections that spread to Canada, Vietnam, and Singapore, and past MERS and Ebola outbreaks have seen a small number of cases leading to a high volume of transmission to secondary cases (Frieden and Lee, 2020; Hung, 2003).

These are all hallmark characteristics evidencing the dangers of failing to contain superspreader events. Similarly, events across the world and as diverse as religious gatherings, cruises, fitness classes, weddings, conferences and political events (including the October gathering at the White House Rose Garden for Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett) have been identified as some of the largest COVID-19 superspreader events (Courage, 2020).

A key question that parallels the real-world epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 superspreader events is whether these same dynamics apply to information transmission online, particularly how online contagion starts and spreads, and what individuals or organizations are behind these “digital outbreaks”. Some early evidence is emerging, particularly in the context of COVID-19 misinformation about drugs, vaccines, and other treatments, which can impact consumer perception and demand for these health products (Morrison and Heilweil, 2020). For example, in progress work by our research lab found that in the period immediately following a misinformation tweet from President Donald Trump about the drug hydroxychloroquine, 84% of 1.2 million tweets we reviewed contained misinformation topics. While the majority of these posts touted the unproven efficacy of the drug for COVID-19, other tweets included calls for increased access (such as a petition for making it over-the-counter) while other users actively inquired how to buy the drug offline and online.

Hence, the spread of misinformation about COVID-19 can have knock-on effects that can lead to greater and unsubstantiated demand for COVID-19-related treatments, including products that may be in shortage, are not approved for use by regulatory agencies or that lack scientific evidence about their safety and efficacy. This can also open the door for fraudsters and counterfeiters who seek to fill the gap between misinformation and ensuing consumer demand that cannot be met by legitimate sources, as evidenced by numerous reports of counterfeit COVID-19 tests, medications, and protective personal equipment being seized by customs officials (CBP, 2020; Sutton, 2020). However, the strategies used by these “influencers” and their impact on public safety has not yet been explored sufficiently in the broader product integrity and anti-counterfeiting area.

Superspreaders and Influencers for COVID-19 Treatments, Drugs, and Luxury Goods

As highlighted by organizations including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime, Interpol and Council of Europe, online scams and the threat of counterfeit COVID-19 products are a significant threat to public health and patient safety (UNODC, 2020). Illustrating this risk, in a study we recently published in the journal JMIR Public Health Surveillance, we scanned the popular social media platforms Twitter and Instagram and used a hybrid machine learning approach to detect illicit online marketing and sales of COVID-19 treatments, testing kits and medications. We detected thousands of posts in infodemic “waves” involving various questionable health products, different types of selling claims and a variety of types of sellers (Mackey et al, 2020).

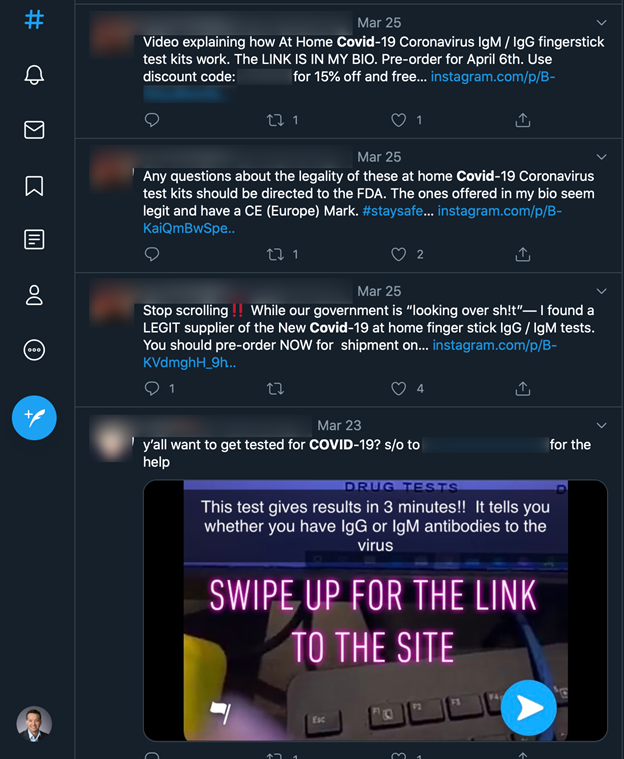

One finding hidden in the results is an outlier analysis we conducted on the detected COVID-19 selling accounts that had the top number of followers and posts in our dataset, in other words, the most influential accounts in the social networks we observed (more than 20,000 followers, including one account we focused on that had 80,000+ Twitter followers). Upon further inspection we identified that this account belonged to an American reality TV star who is a celebrity healthcare practitioner who had over 97,000 Twitter and 1.5 million Instagram followers at the time. The account posted a video about a “At Home COVID-19 Coronavirus IgM / IgG fingerstick testing kit” and a link to preorder the product along with a discount code (no home testing kit was approved at the time for COVID-19) (see Figure 1). Further examination found that the hyperlink redirected to a website for a purported medical supply company that offered the sale of the testing kit but no longer had it in stock at the time of inspection. We do not reveal the identity of the account or linked website here as it has been sent to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for further investigation.

Importantly, though the majority of the COVID-19 seller networks we reviewed appeared to have overall lower levels of interactions with other social media users (based on an analysis of the aggregated social interaction metrics), some actors in the network nevertheless appeared to be highly influential and could represent superspreaders of misinformation and unsafe access to COVID-19 products that were in high-demand at the time. Further, the fact that the “influencer” post we examined originated from a “healthcare professional” and someone with so many followers should be concerning, as online users may trust this individual as a credible source of information and may even take the extra step to click on the link that was provided to buy an illegitimate product.

Some interesting parallels and differences can also be drawn from other product commodities, including our work on illicit online pharmaceutical sales and counterfeit luxury goods (Mackey et al, 2017). Online surveillance for opioid and controlled substance sales have similarly identified social media accounts with a high number of followers (generally between 2,000-20,000) that are actively selling or promoting illegal access to a variety of drugs. These accounts are not monolithic, with some that simply appear to be popular “digital drug dealers,” while others that post about a variety of lifestyle and health topics, and illicit drug sales. Some appear to have promotional relationships, perhaps indicating that these accounts act as marketing affiliates for rogue online pharmacies or fraud-related networks. Lastly, celebrity news events can also be co-opted by illegal sellers. This includes the highly publicized death of emo rapper “Lil Peep”, who died from overdosing on fentanyl and Xanax, but whose image and namesake are often used by online drug sellers when curating and marketing their services on social media (Beaumont-Thomas, 2017).

In the consumer luxury goods segment, social media influencers, who can also act as superspreading accounts, appear to be a vital part of the online counterfeiting ecosystem. One preliminary analysis we conducted on a luxury jewelry brand detected a widely shared Instagram post from an influencer who included a link to her video about how to tell the difference between a fake and real luxury brand bracelet. When further prosecuting the metadata in the profile, it lead to a YouTube account and video detailing the differences between a $24.99 fake version of the bracelet and the $6,750 authentic version and also included links to buy the counterfeit version on Amazon.com. In this case, not only is the social media account influential, but it also provides detailed information valuable to the consumer on how to distinguish between a fake and legitimate product but then enables their purchase of a fake product directly with an online vendor.

Online superspreaders and influencers can be different in their account characteristics, marketing and selling strategies, and how they leverage their online presence depending on the types of products they are selling. These influencers are not new to the study of counterfeiting and product integrity, but are arguably more of a threat when considering the active role they are now playing in dual public health emergencies of the national opioid crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Further Research and Innovation

Our academic research at UC San Diego and our innovation and commercialization activities through our National Institutes of Health funded big data and machine learning startup company S-3 Research LLC, continue to focus on better understanding how these digital superspreaders and influencers can negatively impact public health outcomes (McManus and Mackey, 2020). We are currently running several projects conducting a deep-dive into COVID-19 misinformation and social dynamics, expanding our work on the illicit online drug trade (including analysis in multiple languages for precursor chemicals, synthetic drugs and branded pharmaceutical products), continuing our monitoring of the illegal online wildlife trafficking industry, and conducing social media monitoring to differentiate between legal and illegal cannabis, vaping and tobacco online marketers and sellers. For the COVID-19 pandemic, we are also starting to focus our big data surveillance efforts to vaccine candidates, as existing misinformation about vaccines, concerns about vaccine hesitancy and possible lack of sufficient legitimate access will surely drive demand in the black market.

Innovation in this important area of research and innovation in order to better characterize the impact of superspreaders and influencers needs to accelerate, particularly in the era of Web 2.0. This includes using more advanced approaches of social media analytics analysis combined with machine learning inference, in-depth analysis of digital superspreading events involving misinformation that can lead to greater consumer demand and developing network analysis approaches to better identify and characterize the dynamics of online sellers and their undue influence on online communities.

See Temperature Test Poll

in this edition on influencers

THE BRAND PROTECTION PROFESSIONAL | DECEMBER 2020 | VOLUME 5 NUMBER 4

2020 COPYRIGHT MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES