CRISIS MITIGATION

THROUGH COMMUNICATION IN BRAND PROTECTION

Andy Grayson

Graduate Intern, Anti-Counterfeiting and Product Protection, Michigan State University

Leah Evert-Burks

Managing Editor and Industry Fellow Center, Anti-Counterfeiting and Product Protection, Michigan State University

All organizations are susceptible to widely publicized crises. Brand crises—such as those resulting from the Samsung Note 7 recall, the BP Gulf of Mexico disaster, financial losses and internal corruption at Enron, or Tylenol tampering—can remain embedded in public memory for decades (Coombs, 2014).

Few brands are aware of all the resources (e.g., in-house employees, academic research, practitioner experience) they have to develop their own plans for responding to a crisis. This article seeks to provide brands with, 1) basic guidelines and resources that are essential to developing a crisis-mitigation plan ultimately reflected in crisis communication, specifically in relation to brand protection and counterfeit products, and 2) examples of varying communication approaches some industries have taken to recent product-counterfeiting crises that may have mitigated damage—including some that have actually helped improve sales and communication on companion threats.

Myriad researchers and practitioners study crisis mitigation. As a result, there are many definitions of crises in this area. We use that of Katherine Fearn-Banks, 2007: a crisis is, “a major occurrence with a potentially negative outcome affecting the organization, company, or industry, as well as its publics, products, services, or good name.”This definition encompasses all possible entities a crisis could negatively affect.

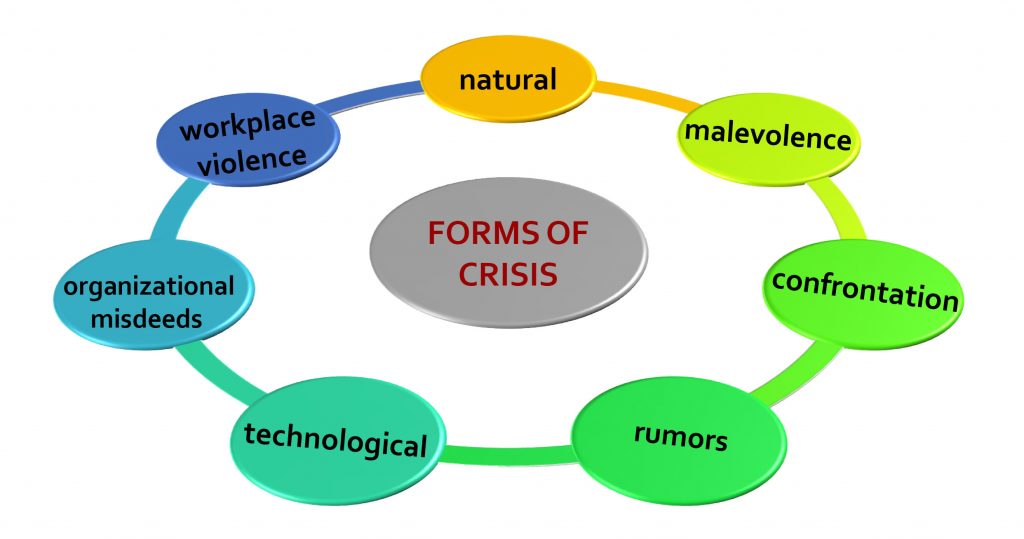

Crises may take various forms: natural, technological, confrontation, malevolence, organizational misdeeds, workplace violence, and rumors (Lerbinger, 1997).Counterfeiting threats can fit into many of these crisis categories. The Enron crisis was a crisis of organizational misdeed and internal corruption, a rumor crisis with actions permanently tarnishing the firm’s reputation, and a crisis of malevolence given the harm caused to the greater economy (CNN, 2013)

Similarly, Samsung has suffered a loss of trust, one of the most detrimental outcomes a brand can face. Product-defect crisis mitigation and communication plans have many analogous elements to brand protection. As one crisis-management executive observed, “Unfortunately for Samsung, when one product is defective, it implicates the entire brand in the court of public opinion.” Furthermore, Samsung “committed the cardinal sin of crisis management by claiming the problem was fixed when in fact it wasn’t” (Lince, 2016).

Most crises are multifaceted and threaten multiple components of a firm. Therefore, it is vital to investigate every aspect of a foreseen or active crisis to ensure that all possible risks are alleviated.

Prior to developing a complete crisis mitigation plan, W. Timothy Coombs (2014) advises that an organization conduct a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis. The SWOT helps identify what an organization already does well (strengths), what the organization lacks (weaknesses), the capital an organization has to prevent and ameliorate crises (opportunities), and the potential hazards to an organization’s success (threats). Coombs asserts that conducting a SWOT analysis allows for ample foresight into and appropriate preparedness for creating a complete crisis communication plan to mitigate damage to the organization.

In addition to a preliminary SWOT analysis, Coombs posits the three-stage approach to developing a crisis mitigation plan: 1) pre-crisis, 2) crisis, and 3) post-crisis.

The pre-crisis stage comprises all things that could help an organization plan for a crisis. Its three factors are, “prodromal signs, signal detection, and probing” (Coombs, 2014, p. 9).

These can aid an organization in detecting any event that may lead to crisis. Internal and external partners to an organization are key to identifying these signs. Researching (probing) all possible avenues by which your organization could be adversely affected by a counterfeit product expedites the identification of warning signs that could occur (signal detection), or symptoms of a crisis that is in its preliminary stages (prodomal signs).

The crisis stage is made up of the measures taken to slow the catalyst event (crisis). Its three main facets are “damage containment, crisis breakout, and recovery”. An organization’s use of in-house PR or communication professionals is critical for navigating these stages; as such personnel will know how to best relay unfavorable information to the public.

Finally, the post-crisis stage includes the learning and resolution sub-stages. The organization must revisit each stage of the crisis and identify what it did well and what it could learn from the crisis (learning), as well as what it plans to do to prevent further crises (resolution). It may also be beneficial for an organization to conduct another SWOT analysis during the post-crisis stage to adequately assess its current organizational standing.

While the above three-stage plan has much value for developing a crisis-mitigation plan, the value of a quick or readily available prepared response in the age of the internet is crucial. Rapid communication is key given the vast speed at which news travels and the many social media outlets by which it can be shared. It is essential for an organization not to waste any time determining the content of the messages or who should receive them.

Looking in from the outside

Several crises surrounding counterfeit products, and subsequent corporate responses, provide insight on how to effectively respond. Below we review corporate communication regarding counterfeit pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and auto parts.

Due to the immediate health and safety concerns they pose, some high-profile pharmaceutical counterfeit cases have dominated reports in the media. In the past year, there has been an unprecedented increase in the number of incidents involving counterfeit opioid-based medications (Kamp & Campo-Flores, 2016). In fact, counterfeit opioids may have led to the April death of the musician Prince (Brodwin, 2016). In particular, criminal opportunists counterfeiting opioids are adding deadly doses of the synthetic narcotic fentanyl. Fentanyl was first added to illegal heroin. However, it is now being added to counterfeit prescription drugs to mimic narcotic effects at lower costs to capture illicit profits related to the painkiller epidemic.

In one recent case, a San Francisco couple set up a profitable lab in their apartment to produce counterfeit pills (Kamp & Campo-Flores, 2016). Mallinckrodt, the manufacturer whose products were counterfeited, only responded after news of the lab was published, and then did not issue a press release or information other than statements of cooperation with the authorities. In addition, the organization did not provide information on the counterfeit pills or how to identify them. Rather, this information came from health authorities such as Drug Enforcement Administration and state authorities such as the California Poison Control. Similar after–the-fact limited communication plans appear to be the choice of other manufacturers in the opioid industry. Such crisis-stage reaction may be grounded in the hope that the crisis and residual brand-association diminishing with time—but only time will tell if this response serves well as damage containment, crisis breakout and recovery.

Similar to counterfeit pharmaceuticals, counterfeit cosmetic products can also pose health and safety concerns given their application to the skin. In a recent case, counterfeit MAC and Chanel products were found to contain harmful levels of lead, beryllium, aluminum, and bacteria (Somosot, 2014). MAC had a pre-crisis and crisis plan approach. Its pre-crisis approach included providing information to consumers on its website (MAC Cosmetics Counterfeit Ed) and acknowledging the prodromal signs, signal detection, and probing factors. These sought to prevent counterfeit purchases by providing essential information and re-directing sales from counterfeiters to authorized retailers. Its crisis approach included a press release following a 2014 report by ABC’s Inside Edition on counterfeit products. Its planning and quick response allowed MAC to direct consumers and press to information immediately after an event occurred. This may boost sales of its valid products, especially as consumers come to appreciate MAC’s transparency and readily retrievable information.

The automotive industry provides a third example of responses to counterfeit products. This industry often must communicate on genuine-part quality recalls and non-genuine-part counterfeit alerts. Hyundai, which has been subject to recent recalls for products such as defective Takata airbags, sunroofs, and instrument-panel features, has taken an onstage approach to communication on counterfeit airbags and unauthorized parts in combined messaging (Huetter, 2016). This messaging both warns consumers of counterfeit parts and urges them to request genuine Hyundai replacement parts, thereby combating the lucrative practice of using imitation aftermarket parts in collision repair and fixes. The company also publishes a web page (ConsumerAwarenessHyundai) for consumers on crucial brand issues. This information is readily available to the press and the public should a crisis arise.

When a mass-media story breaks out about a high-profile raid or companion crises such as product defects or recalls that a brand has been counterfeited, brand owners must be ready with a crisis plan. Understanding guidelines for crisis communication will help in developing a plan and in framing an appropriate response. How a brand responds to a crisis, both through the content of its communication and its transparency, can influence public opinion on it.

THE BRAND PROTECTION PROFESSIONAL | DECEMBER 2016 | VOLUME 1 NUMBER 2

2016 COPYRIGHT MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES