Guiding Law Enforcement, Prosecutors, and IP Rights Holders in Europe with John Zacharia

John Zacharia is an attorney with extensive experience in IP investigations and prosecutions. He previously worked at the U.S. Department of Justice, where he served as the Assistant Deputy Chief for Litigation of the Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section (CCIPS). Now in private practice, John counsels clients on addressing intellectual property violations, cyber threats, and represents them in domestic and international commercial litigation and administrative law actions. John is also a member of The Brand Protection Professional Editorial Board.

Readers will recall that we spoke to John previously, in the 24th edition of the Brand Protection Professional, on Understanding Artificial Intelligence and Enforcement of Rights following the work he did on co-authoring the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) study on the “Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Infringement and Enforcement of Copyright Designs” issued in March of 2022. We also spoke with John in the 20th edition of The BPP, on Deep Dive into International Cooperation Tools for Brand Protection following the work he did on co-authoring the EUIPO study on the “International Judicial Cooperation in Intellectual Property Cases” issued in March of 2021.

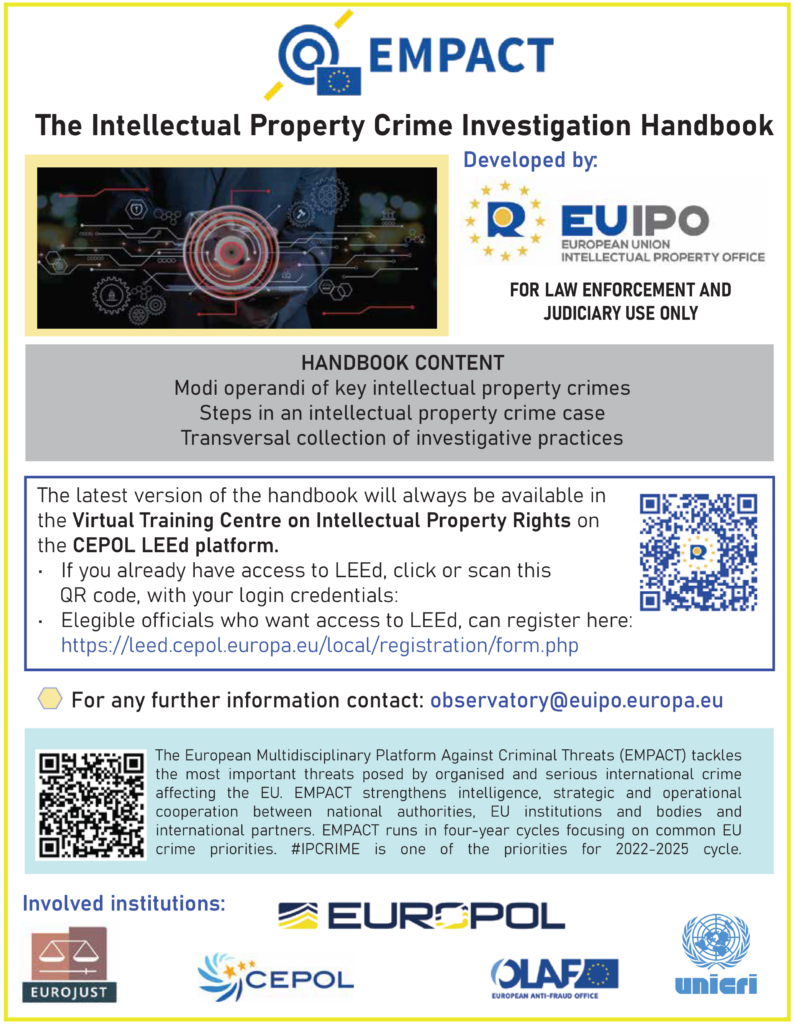

Now, we will talk to him about two additional publications he has worked on for the EUIPO; both guides, “The IP Crime Investigation Handbook” (Handbook) and an IP rights holders guide, focused on criminal referrals. Though the first guide is intended for law enforcement only, covering trademark counterfeiting and copyright infringement, and not for public viewing, he will walk us through some of the aspects covered in the guide. We will also provide information to our law enforcement readership on how to access the guide through required credentials; for the second guide, he will provide a preview as this guide is intended to publish in the first quarter of 2024. This will be publicly accessible and help guide brand owners on how to best prepare a criminal referral of trademark counterfeiting, copyright infringement, and trade secret theft cases to law enforcement.

THE BRAND PROTECTION PROFESSIONAL | JUNE 2023 | VOLUME 8 NUMBER 2

2023 COPYRIGHT MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES

- Next…