Indigenous Rights:

Awareness & Best Practices for Appreciation vs. Appropriation

Image Credit: “Laxman Ji Ki Satya Pariksha” by Ram Singh Urveti

Michael Pampalone

Pampalone Law (USA)

Rohan Rohatgi

RSR Legal, Advocates (India)

Modern technology has facilitated the evolution of an ever-more interconnected and global marketplace, leading to greater accessibility, on the part of businesses and consumers, to valuable cultural ideas, expressions and knowledge that, in the past, may only have been available to a select few. Along with this heightened age of interconnectivity, there has arisen a greater awareness of, and appreciation for, the Traditional Knowledge (“TK”) and Traditional Cultural Expressions (“TCEs”) of Indigenous Peoples globally. In many instances such TK and TCEs were garnered and developed over millennia, are sacred and are interwoven into the very identities of Indigenous Communities from which they arose. While this increased appreciation for TK and TCEs promises many fruitful opportunities for businesses, there are challenges that businesses must meet, and hazards they likely want to avoid, in utilizing TK and/or TCEs in the products they market and sell (and/or the services they render) to ever-increasingly knowledgeable and well-informed consumers. In the absence of readily applicable laws in many parts of the world, provided here are some basic guidelines to assist in navigating the line that exists between “appreciation” and “appropriation” when it comes to utilizing TK and/or TCEs in the global marketplace, to set a pathway for businesses to partner with Indigenous Communities in an ethical and mutually beneficial manner. Further to this purpose, we point to two examples taken from the fashion and entertainment industries that illustrate what can go wrong, and what can go right, when businesses utilize TK and TCEs.

Carolina Herrera Crosses the Border of Appropriation

It seems unlikely that world-renowned fashion brand Carolina Herrera foresaw the storm of controversy that it was sailing into when it released its resort 2020 collection, much of which utilized patterns and embroidery techniques that embody the TK and TCEs of Indigenous Mexican communities. However, despite there being no clear violation of any applicable laws in effect at the time, the brand was quickly engulfed in a maelstrom of outrage on social media when it released its collection, culminating in the receipt of a letter from the Mexican government accusing the brand of cultural appropriation in the collection. While the brand’s designer (eventually) attempted to frame its utilization of these traditional patterns and embroidery techniques as a “tribute” to the Indigenous Peoples from which they were taken, this did little to quiet the controversy that was ignited. While there are numerous other brands that have made similar missteps in recent years, Carolina Herrera is frequently pointed to as a cautionary tale of what can happen when a business crosses the line between “appreciation” and “appropriation” of TK and/or TCEs and may have served as the catalyst for the Mexican government passing a law aimed at protecting the TK and TCEs of its Indigenous Communities.

What could Carolina Herrera have done differently? Initially, it could have been open and transparent regarding the “inspiration” behind its collection, taken steps to identify the Indigenous Mexican communities from which these distinctive patterns and embroideries emanated and sought to partner with these communities in creating, marketing, and selling the collection to consumers in a manner that would provide for proper attribution and a share of financial compensation. While engaging in these steps and overcoming the challenges in identifying and ethically partnering with Indigenous Communities may seem to be an insurmountable task in some instances, the rewards reaped in properly utilizing these valuable patterns and embroidery techniques, along with the potential public relations and marketing benefits, may have greatly outweighed the additional effort involved in doing so. Another option would have been to refrain from incorporating any patterns and/or techniques and embroideries in the collection, which would require the identification of any inspirational TK and/or TCEs during the design of the collection and a prospective willingness to err on the side of caution in making sure that such TK and/or TCEs were not incorporated into the collection. This, at the very least, may have allowed Carolina Herrera to avoid a perfect storm of negative publicity, which takes us to our next example (See also Misappropriation of Traditional Knowledge and Traditional Cultural Expressions).

Disney Charts a Course Towards Appreciation and Cooperation

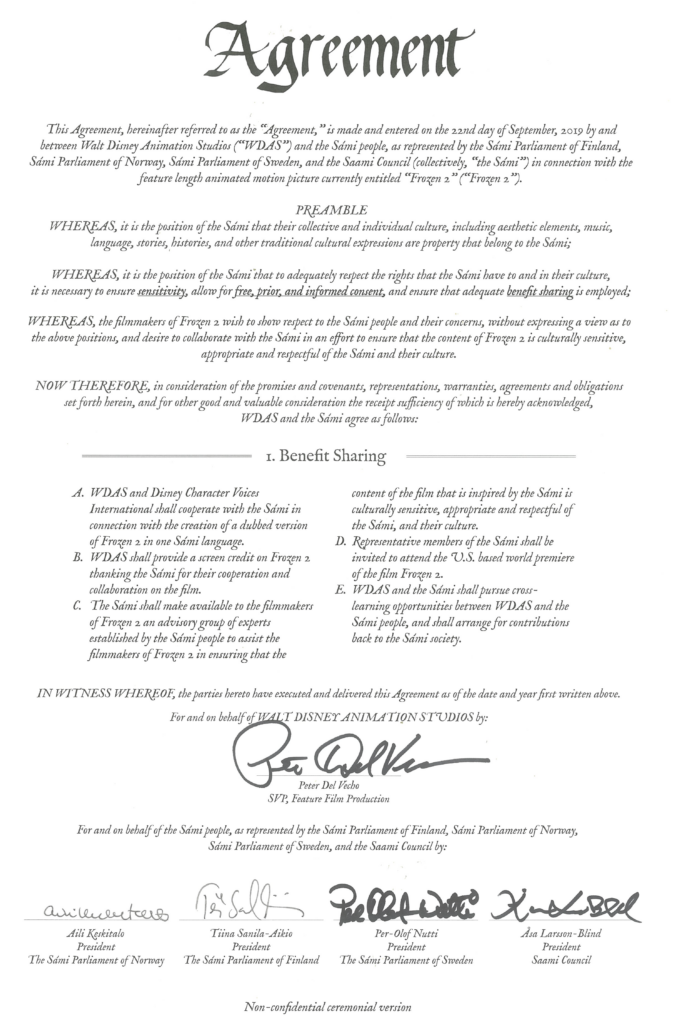

After the immense financial success that Disney Animations Studios (“Disney”) realized in connection with the release of its animated film Frozen, which was inspired by the culture of the Sámi people, indigenous to the Scandinavian and Kola Peninsulas (in modern day Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia), the producers of its sequel Frozen 2 came to a crossroads. Representatives of the Sámi people reached out to Disney after the release of the original film and voiced their concerns regarding the manner in which Sámi culture and history are presented; Disney was faced with the choice of either seeking to minimize the importance of the elements of Sámi culture that inspired the original film or embracing the TK and TCEs of the Sámi people as important contributions to the unquestionable success that Frozen continues to realize.

Perhaps informed by Disney’s prior experience with the film Moana, which faced stiff criticism for its portrayal of Indigenous Polynesian culture, the producers of Frozen 2 chose to chart the latter course in recognizing the essential role that Sámi cultural influence played in the success of the original film and realizing the opportunity to build upon that success in partnering with the Sámi people in moving forward with the franchise. Disney and the Sámi people were able to achieve a mutually beneficial result by actively negotiating an agreement that was put into place, pursuant to which the Sámi people had a vehicle to voice and address their concerns regarding the portrayal of their cultural treasures that facilitated cooperation between the filmmakers and Sámi representatives.

While the full terms of the agreement reached between the parties remain confidential, among other terms, the publicly available “ceremonial” version of the agreement (Disney/ Sámi Agreement, 2019) provides for close consultation with the Sámi people regarding the portrayal of their culture and history, educational opportunities for members of the Sámi community, screen credits, the film being dubbed into the North Sámi dialect and “contributions back to the Sámi society.” It has also been reported that Disney agreed to pay the Sami people a portion of the film’s profits (McGwin, 2020).

In this instance, organized representatives of the Sámi people voiced their concerns to Disney and were able to engage in productive negotiations on behalf of their communities, meeting Disney in what would seem to be much more than half-way to achieve, by all accounts, a mutually beneficial resolution. The unified approach that the Sámi people were able to make in addressing the concerns of their communities and the lessons Disney learned in facing backlash for claims of cultural exploitation and insensitivity may well be the most impactful factors that brought about this result. This is particularly true given the difficulties that businesses may face in identifying the Indigenous communities and people that lay valid claim to originating (and caretaking) certain TK and TCEs. Regardless, there are valuable lessons to be taken away with respect to the importance, and prospective rewards, of utilizing TK and TCEs in a proper and ethical manner, which Carolina Herrera appears to have had the opportunity to learn in a similarly hard way.

These lessons help to illustrate the need for businesses to incorporate suitable steps into their best practices in order to: (i) identify any TK and/or TCEs that may serve as inspiration for their products or services; and (ii) engage with the relevant Indigenous Communities with the goal of achieving a partnership that governs the use of their knowledge and/or expressions in a mutually beneficial and culturally appropriate manner prior to making use of them.

THE BRAND PROTECTION PROFESSIONAL | DECEMBER 2022 | VOLUME 7 NUMBER 4

2022 COPYRIGHT MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES

- Next…