INTERNATIONAL CHAMBER OF COMMERCE (ICC)

RISK ASSESSMENT ON THE IMPACT OF SUPPLY CHAIN SECURITY PRESENTED BY THE CORONAVIRUS OUTBREAK

Bruce Foucart

Deputy Director, ICC Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy (BASCAP)

Michael Ellis

Policy Advisor, ICC Business Action to Stop Countfeiting and Piracy (BASCAP)

Special Note

In mid-March 2020, the ICC and the World Health Organization (WHO) announced an unprecedented collaboration in calling businesses to action in the fight against COVID-19. This agreement leverages the ICC’s global network of over 45 million businesses to enable companies worldwide to play an active role in preventing the spread of the COVID-19 outbreak. It calls for ICC and the WHO to regularly facilitate information flows by disseminating the latest and most reliable information on the COVID-19 outbreak to businesses. It also calls for national governments to adopt a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach by making all necessary resources available in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

ICC has launched a web portal dedicated to providing businesses, policymakers and chambers of commerce worldwide, the latest and most reliable information on the COVID-19 outbreak. Access to the web portal, developed in line with ICC’s commitments to the WHO, can be found here in addition to a list of ICC’s COVID-19 business response activities to date.

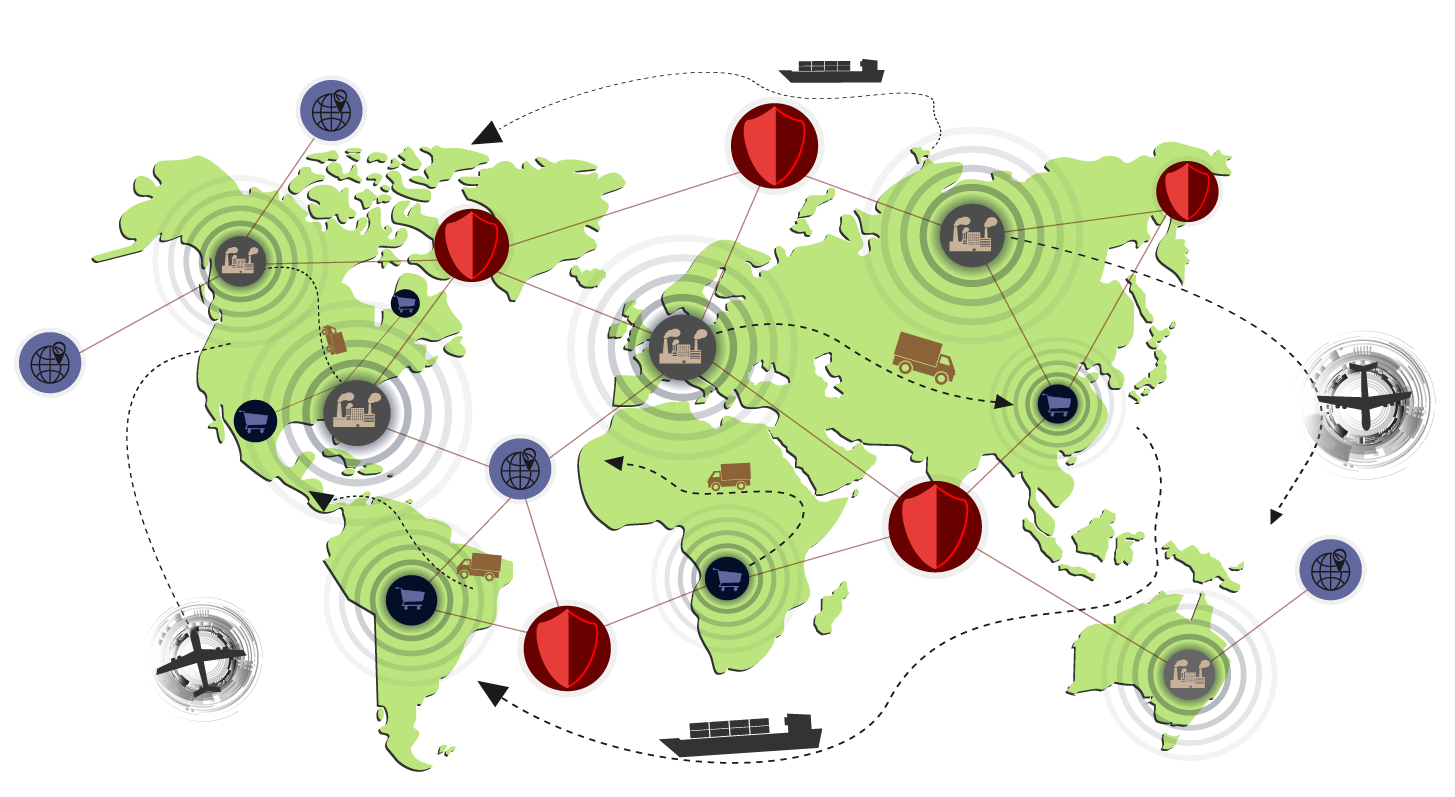

Supply chain security remains a high priority for any business involved in global trade. Breaches in the legitimate supply of trade will often damage or disrupt legitimate business, leading to unnecessary costs, inefficient delivery schedules and a risk to intellectual property.

There are generally two kinds of supply chain threats, antagonistic and non-antagonistic. Antagonistic threats are deliberate or caused illegally as defined by law, and sometimes a consequence of hostile acts, such as a terrorist event (Banaitiene, 2012).

Non-antagonistic threats to supply chain security are often unforeseen in nature, such as those related to catastrophic weather, hurricanes, floods and typhoons, or as in the case of the coronavirus, health related incidents (Ekwell, 2012).

The top ten supply chain impacts in recent years include acts of war, and climate change but more relevant to this risk assessment are product recall, economic uncertainty and material shortages (Larsson and Kamal, 2019).

The existing coronavirus (2019-nCoV), officially named as Covid-19 by the WHO, at the time of this report (April, 2020) has spread to over 100 more countries apart with a total of over 3,325,000 confirmed cases of coronavirus infection including 234,496 deaths worldwide, in particular country hotspots including China, Iran, Italy, Spain and USA (Worldometers, 2020).

Some within the public have understandably responded to the existing threat of the coronavirus with irrational fear, despite expert advice from national governments and international organizations including the WHO on how to manage the threat.

The ICC believes this growing fear brings with it opportunities for organized criminal groups to infiltrate the food supply chain and supply of medicines. We have already seen numerous law enforcement seizures of counterfeit coronavirus testing equipment, and personal protection equipment (PPE) (City of London Police, 2020).

As shortages in legitimate supply drives higher demand for products such as foodstuffs, this in turn allows for adulterated foods to enter the supply chain. The shortage is caused by many reasons including interruption in genuine supply, shortages in the shops, and in steep increase in prices, as “racketeering” opportunities. Experts in investigating and managing food fraud investigations in many parts of the world report that shortages and demand provides opportunities for an increase in the manufacture and distribution of counterfeit and adulterated goods, manifested and driven by consumer’s needs or perceived need in time of crisis. ICC-BASCAP has publicly noted that the pandemic has provided the opportunity for criminal elements to exploit shortages in genuine foodstuffs and similarly other household goods to distribute fake and adulterated goods.

The WHO reports that unsafe food creates a vicious cycle of disease and malnutrition, particularly affecting infants, young children, elderly and the sick. Unsafe food containing harmful bacteria, viruses, parasites or chemical substances can cause more than 200 different diseases — ranging from diarrhea to cancers. Around the world, an estimated 600 million — almost 1 in 10 people — fall ill after eating contaminated food each year, resulting in 420,000 deaths. The WHO also states that in addition to contributing to food and nutrition security, a safe food supply also supports national economies, trade and tourism, stimulating sustainable development (World Health Organization, 2020).

Another threat observed within the food industry is the commercial impact faced by a potential shrinking customer base, given the closure of places such as restaurants, shops, offices and reductions of public travel. It has being widely reported that the coronavirus outbreak is driving up the cost of food, and while demand increases due to lack of supply, the pressure on household budgets also increases. A rise in consumer price inflation at 5.4% in January by the National Bureau of Statistics for China and that consumer prices are increasing at their fastest rate since October 2011 (EFE, 2020).

This is a concerning trend as our experience tells us that once there is a drive in increased prices and increased shortages, suppliers will be tempted to take short cuts in their processing and product supply chains, leading to either counterfeit foodstuffs entering the markets and/or adulterated foods appearing on the shelves, having been “bulked” with unauthorized agents.

On March 31, 2020, the National Customs Service in Chile seized over 1.1 million food supplement capsules valued to be over $15,000 at port of entry in Chile. The cargo originated from Ningbo, China, and arrived at San Vicente port in the Region of Bio Bio. Talcahuano Regional Customs, based on the risk profiles and documentary analysis, detected the fraudulent import, not excluding the possibility that the mentioned supplements might contain ingredients with harmful effects for the consumer’s security and health. The Chemical Laboratory from the National Customs Service in Valparaiso and the Institute of Public Health (ISP), concluded that other toxic components such as yohimbine and sibutramine were found in the retained goods (React, 2020).

Continuing to use China as an example because they were the first country to experience the coronavirus, sales of food items make up nearly a third of spending by Chinese consumers, and of all consumer goods foodstuffs spiked the most during the crisis. For example, because meat products were already under pressure because of a devastating pig disease with prices rising fast, the government released over 100,000 metric tons of pork and 47,000 metric tons of vegetables from its central reserves since the coronavirus outbreak began to curb demand (South China Morning Post, 2020).

The Chinese Central Government Bureau of Statistics has already publicly acknowledged that the consequences for the continuity of the international food supply chain is immense, given the role the coronavirus has played in causing prices to surge, coupled with travel restrictions, closure of factories, restrictions on workers travelling and other preventative and control measures (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2020).

Other Affected Supply Chains

Businesses have also experienced one of the most substantial negative supply chain security effects of the coronavirus; global trade. Maritime imports and exports are down as the demand for maritime shipping is dwindling due to the shortage of goods, products and parts exported by China, the first to be effected by the coronavirus.

While eighty percent of the world’s goods are moved by ship, ships calling at or through major Chinese ports had fallen 20% since January 2020, maritime data provider Alphaliner said, as measures to control the coronavirus outbreak cut into international supply chains (The Wall Street Journal, 2020).

Because of the coronavirus, the world experienced major shortages of specific products such as pharmaceuticals and/or essential ingredients, medical devices including the coveted N95 face masks and latex gloves, plus automobile parts and crude oil. Numerous factories making these products have had to close and have been slow to open back up. At the time of this writing it is not known when factory workers globally will return to full capacity that can make up for the shortages.

ICC believes that the long term affects of the lack of genuine products and supplier disruption will continue to be devastating to legitimate business, with declining supply chains, and reduced production to adjust to decreasing supply of raw material. Each level of the supply chain will see a decline in demand which will have a domino effect on all those within the supply chain, with the most vulnerable companies leveraging suppliers upstream, who are in danger of failing.

Likewise, retailers directly affected by the lack of consumers due to closed businesses will likely experience drops in demand for their product and as such will carry high inventories and eventually cut orders to the supplier, then wholesaler, then manufacturer and so on.

Unfortunately, many companies will learn from this pandemic how unprepared for this type of supply chain disruption they are. There will be an immediate recognition to reduce dependency on certain countries as suppliers, and one immediate reaction may be to either relocate production companies, or find qualified suppliers in other parts of the world, which will be costly.

Additionally, many analysts suggest that demand in other countries such as Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia is already increasing and they simply cannot handle any more business.

However, diversifying production within a company’s supply chain is the right approach for the future, as supply chains must remain agile. In addition to production costs, companies must now closely consider many factors including safety, long-term economic stability, costs of tariffs and duties as well as how a country respects intellectual property rights.

Many businesses may now need to acknowledge the existing risks and minimize their exposure to future disruptions, using supplier development teams to identify alternative first, second and third-tier suppliers, without such a dependency on certain countries such as China, as they review their suppliers’ inventory statuses regularly and maintain communications with country authorities.

“ICC-BASCAP is also contributing to enhancing information flows regarding the coronavirus outbreak by surveying its global private sector network to map the global business response. This will both encourage businesses to adopt appropriate precautionary approaches and generate new data and insights to support national and international government efforts.”

Please take 5 minutes of your time and take the following survey that will help us with the above efforts.

Bruce M Foucart is an independent consultant and co-owner of Foucart & Associates, Inc. He is a former Special Agent of Homeland Security Investigations and was the Director of the U.S. Intellectual Property Coordination Rights Center from 2014-2016. Bruce now serves as the Deputy Director of the International Chamber of Commerce’s Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy. He provides trade based financial crimes training to international law enforcement and is also a Fellow of the Michigan State University’s A-CAPP Center.

Michael Ellis currently acts as a consultant for Ellis and Associates (Global) Ltd and policy advisor for ICC-BASCAP. He is a former UK Detective and up until 2016 was Assistant Director of Illicit Trade at Interpol, where he helped coordinate the organizations response to illicit trade across the Interpol member countries. He is a Fellow of Michigan State University A-CAPP Center, and is a Senior Advisor to the Swiss based “Cross-border Research Association” (CBRA), which advises the EU Commission on advanced supply chain security and crime prevention measures.

THE BRAND PROTECTION PROFESSIONAL | JUNE 2020 | VOLUME 5 NUMBER 2

COPYRIGHT 2020 MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES